Welcome to the M2M Blog

Roger The Blogger

My name is Roger and I’ve been an amateur musician since junior high. Sounds like introducing myself to people at some 12 step program. Maybe it is. I also have a home business repairing stringed musical instruments, although I have been doing less and less of that, by choice. I’ve made guitars and learned to play quite a few instruments, playing some of them reasonably and some poorly. I have an advanced degree and know something about chemistry, physics, and electronics.

From about 1995 to 2004 I played violin, mandolin, and pennywhistle with the Tucson Friends of Traditional Music’s Slow Jam, its successor, and one spinoff. At the Slow Jam I met Catherine and limell’. They introduced me to the Mount Lemmon Marching Mandolin Band, and later to the String Bean Folk Orchestra (SBFO). In 2009 I joined the SBFO, playing a banjo tuned an octave below the mandolin. Lately I’ve been playing violin III and clarinet. After a layoff of about 30 years, I’m back on woodwinds. Yay!

In 2010, Catherine started Minute2Minute (M2M), with me on clarinet, bass clarinet, penny whistles, and, lately, ocarina. I have begun typesetting music by computer and arranging a few pieces for performance by both M2M and the SBFO. Maybe we’ll introduce the tarogato. (I have one, and can play it, but you should Google tarogato to figure out what it is. For that matter, you should Google the ocarina.)

Some of what I will write in this blog concerns the technical aspects of musical instruments. Some will be background into the history and evolution of musical styles, and some will be music theory. I do not claim to be a musicologist, but I know how to do research and how to be skeptical about what I read, especially on the internet. I will present literature references for my source materials and will indicate which are my conclusions and which are those of the experts.

--------

Musical Origins: The Basso

The Basso is an upbeat tune that we perform every chance we get. The tune is sometimes listed as a "Universal Gypsy tune."

We love it because it's upbeat and slightly exotic at the same time. Unfortunately, we don't know much about its origins, but we'd like to know more.

Perhaps you know someone who can enlighten us? Anyone?

In an upcoming post we will examine whether there is really a Basic Gypsy Chord Progression.

Tom Dukes and Roger Sperline playing El Basso in 2014

We'd love to hear your thoughts on this. Please join the conversation on our Facebook page. (https://www.facebook.com/m2mtucson/)

-----------

Music Theory &

Exotic Scales: Part 1

The A natural scale

M2M plays many pieces in unusual, minor, exotic sounding scales. In order to understand the differences among, say, Klezmer scales or Andalucian scales, and Major scales, we’ll look at how they are constructed, beginning with Major and proceeding to the more exotic. We’ll stick to musical scales based on western ideas of 12-tone chromatic scales (no micro-tones).

My opinion is that keeping track of the "semi-tones" between intervals is easier than learning all the scales by rote, or whether or not the 3rd and whatever steps are flatted. If you are serious, you should learn both the semi-tone and flatted interval methods.

Major Scale The familiar Major scale ascends and descends using the same notes. Starting on C, playing only the white keys on the piano, these would be C,D,E,F,G,A,B,(c). Starting on D, these would be D,E,F#,G,A,B,c#,(d). We’ll put “interval” numbers on them as 1 to 8 and look at the number of semi-tones between them. A semi-tone is the smallest separation between notes on the piano. I’ll also use part of the convention that upper case letters signify a lower octave and lower case letters signify a higher octave.

C Major Scale: C, D, E, F, G, A, B, (c).

Interval: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

Semi-tones: 2 2 1 2 2 2 1.

Another example:

D Major Scale: D, E, F#, G, A, B, c#, (d).

Interval: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

Semi-tones: 2 2 1 2 2 2 1.

Natural Minor Scale The familiar natural minor scale ascends and descends using the same notes as its “relative” major scale, but starts at a different place in the sequence. For instance, A Natural uses only the white piano keys but starts and ends on A. (A is the 6th step of the relative C major scale – see the diagram above). You will also see this described as “the same notes as A major with the 3rd, 6th, AND 7th flatted”. (That's what the b means in the diagram below.) See pianoscales.org

A natural minor: A, B, c, d, e, f, g, (a).

Interval(rel to A Maj) 1, 2, b3, 4, 5, b6, b7, 8

Semi-tones: 2, 1, 2, 2, 1, 2, 2

Notice that the semi-tone sequence has just been rotated (last became first, first became second, etc.), because we played the same notes in the same sequence but started in a different place.

In Part 2, we’ll get into other types of scales that are heard less frequently in western music, but which are central to exotic sounding music.

We'd love to hear your thoughts on this. Please join the conversation on our Facebook page. (https://www.facebook.com/m2mtucson/)

-------

Musical Origins: Amari Szi

"Amari Szi” is a Roma song about a family welcoming their new daughter-in-law into the fold. This song comes to us thanks to a German band called Csókolom. (pictured below)

The song caught Catherine’s attention while touring with The Mollys in 1999, at the Chimera Music Festival in South Australia. She heard it performed by Csókolom and it was love at first listen. She was intrigued with the song, especially the performance by Anti von Klewitz.

There are many wonderful Roma songs, with lyrics, and many with video performances, on that site.

M2M performs Amari Szi in a rather straightforward E minor, where the chords are Em, Am, D, G, B in part A, and Em, Am, D, G, Am, B, Em in part B. The scale seems to be E natural minor. That would be the same as the Mode known as E Aeolian. The traditional American song “Poor Wayfaring Stranger” is in natural minor.

We'd love to hear your thoughts on this. Please join the conversation on our Facebook page. (https://www.facebook.com/m2mtucson/)

--------

Music Theory &

Exotic Scales: Part 2

C'mon, it isn't that bad, is it?

Last time I showed a way of looking at Major and Natural Minor scales from an interval/semi-tone viewpoint. This time we’ll look at how to get to some important, lovely, exotic sounds based on the Harmonic Minor Scale.

Harmonic Minor Scale: This minor scale is not played using the same notes as any major scale, relative or not. Unlike the natural minor scale, 3rd and 6th are flatted from the relative major scale, but the seventh is not. The scale is played the same ascending and descending. Later we’ll see a minor scale that is different ascending and descending.

The harmonic minor scale in A looks like this:

Ascending or descending: A, B, c, d, e, f, g#, (a)

Interval (rel to A maj): 1, 2, b3, 4, 5, b6, 7, 8

Semi-tone intervals: 2, 1, 2, 2, 1, 3, 1

The “augmented 2nd” interval consisting of 3 half steps is what makes it seem exotic. This scale is often used in Klezmer and Eastern European music. Examples include; “What Are You Doing The Rest of Your Life” by Michel Legrand, “Girl” by John Lennon, "Besame Mucho" by Consuelo Velázquez, and “Hava Nagila”.

Take the IVth mode of the regular Harmonic Minor – that is, start on the fourth interval.

Harmonic Minor: C, D, Eb, F, G, Ab, B, c

Interval (rel to C maj) 1, 2, b3, 4, 5, b6, 7, 8

Semi-tones: 2, 1, 2, 2, 1, 3, 1

Take the IVth mode of that (start on F if it was C Harm Min) to get the Romanian Minor scale:

Romanian Minor: F, G, Ab, B, c, d, eb, f

Interval (rel to F maj) 1, 2, b3, 4#, 5, 6, b7, 8

Semi-tones: 2, 1, 3, 1, 2, 1, 2

(You can think of this as a key signature of Ab and Eb, and start on the note F.)

This scale is used extensively in Klezmer and Jewish music (known as Mi sheberach or Misheberak), and is common in both Romanian and Hungarian folk music. See “The Pinewoods International Collection,” Tom Pixton, NightShade Publications.

Spanish Gypsy Scale (aka ''Phrygian Dominant'') is just the Vth mode of the regular Harmonic Minor.

Harmonic minor Semi-tones: 2, 1, 2, 2, 1, 3, 1

Spanish Gypsy Semi-tones: 1, 3, 1, 2, 1, 2, 2

So, starting on C... C, C#, E, F, G, Ab, Bb, c

(You could imagine a key signature of Ab, Bb, and C# and begin on C, or a signature of Bb, Eb, and F# and begin the scale on D.)

''Phrygian Dominant'' is used extensively in Flamenco and sometimes in Heavy Metal (of all things). I will discuss Phrygian, Phrygian Dominant, and Dorian in upcoming blogs about Flamenco.

In Part 3, we’ll look at the Double Harmonic Major, Hungarian Minor, and Melodic Minor scales.

We'd love to hear your thoughts on this. Please join the conversation on our Facebook page. (https://www.facebook.com/m2mtucson/posts/812436872293184)

--------

Musical Origins:

Indifference or Kozony

M2M calls this piece “Kozony”, which is Hungarian for “Indifference”.

Everyone except Terri is pretty indifferent, but that isn't the kind of indifference we want.

Indifférence (Valse Musette) was composed by Joseph Colombo and Tony Murena. Tony Murena et Son Ensemble Swing recorded Indifférence in 1942, with brothers Etienne "Sarane" Ferret and Pierre "Barro" Ferret on guitar. Murena was featured on accordion. The Ferret brothers, earlier, played with Django Rheinhardt in the Hot Club of France. Some this can be heard on YouTube.

According to Wikipedia: Musette dance forms arose (in Paris, beginning in 1880 and continuing into the 1930s) from people looking for easier, faster, and more sensual dance steps, as well as forms that did not require a large hall. "Musette-forms" that established themselves as variations to popular dances of the day include: tango-musette, paso-musette, and valse-musette, with a special variation called la toupie ("the top"), where dancers are very close and turn around themselves very regularly. An original musette dance also appeared, known as java. The accordion was later substituted for the bellows-blown bagpipe locally called a "musette.”

Wikipedia: Antonio Muréna was born in Borgo Val di Taro, Italy. His family emigrated to France in 1923 and settled in Nogent-sur-Marne. His uncle gave him his first accordion and he began a performing career assisted by his cousin Louis Ferrari. Muréna played in cabarets and music halls from an early age.

Muréna composed works including: “Passion”, “Indifference” (co-written with Joseph Colombo), “Jockey Club”, and “Ping Pong.”

We'd love to hear your thoughts on this. Please join the conversation on our Facebook page. (https://www.facebook.com/m2mtucson/posts/819177628285775)

--------

Minute2Minute trivia:

Part 1

We're often asked, "How did you get this disease?" and, "How will it affect your loved ones?"...

Affecting my best John Wayne accent and quoting John Lee Hooker, "Well, pilgrim...let that boy boogie-woogie, it's in him and it got to come out."

So, to be philosophical about it, getting the M2M disease is part karma and part biology. That bit about how "it got to come out" might explain both why I avoid acupuncture and my unnatural fear of staplers.

As for as how it will affect one's loved ones: Well, pilgrim, at first they will become groupies and pack the tables at the bars and restaurants where we play. The restaurateurs will be ecstatic. The loved ones will offer to schlep the audio gear until they learn that most of the work consists of unsnarling and coiling mic cables late at night, then they'll magically disappear leaving half the cables on the floor. Then they will remain groupies and learn to coil cables late at night and where things go in Catherine's tiny car so everything fits and the restaurateurs will remain ecstatic. THEN they'll learn that if they merely ask, we will play Start Wearing Purple again and again until everyone is ecstatic even if there are no restaurateurs or mic cables involved.

Another thing we have been asked is why we don't have a regular violinist playing with M2M. This, of course, begs the question of whether or not there are any regular violinists, but the real answer is that none of them will play with us.

Better watch your back, Nick, I'm gaining on you!

Similarly, why don't we have any banjos? (banjoes??) There was that unfortunate incident at our very first public gig where, by request, we played a tune on 5 banjos. We had borrowed (I hope those were borrowed but I didn't ask) enough banjos and practiced just enough to get by. Fortunately, a GREAT deal of alcohol was involved on the part of the audience and NONE on our part, so none of our faux pas were noticed. We weren't embarrassed by the banjo experience as much as by our incompetence, but we haven't wanted to relive it.

P.S. The requester and the audience loved it.

I recently had my debut as a percussionist, playing (sort of) tupan and doing some tambourine whacking in medieval style for a school program. It is all very hard to get right. Not only does the tempo need to be spot-on, but the individual strokes have to be intentionally hard or soft to suit the beat or off-beat, rather than like a steamer trunk rolling down a flight of stairs. Our own Nick has mastered it all (not the steamer trunk part.) Huzzah! Huzzah!

I also gave a very short demo of the medieval hurdy-gurdy, then played a 13th century piece. What really made my performances come alive, of course, was the hat. Medieval muffin hat with peacock feather; warm without weight, stylish without ostentation.

Cover coming off the medieval hurdy-gurdy I built. Note the miracle hat with magic feather.

It is not widely known that M2M's success throughout the years is actually due to the extensive use of appropriate headwear. Because the finer arts of millinery and haberdashery are, let us say, extinct, we now bow to the tastes of Jeanne (our Stage Madame) and Catherine "El Bossa" (our fearless leader). Here is a Gallery of examples.

Of course, I'm saving the really choice photos for other purposes. On the other hand, although I love all of my band mates, I don't know what kinds of photos they have of me.

Nick and Pinko.

Brian doing Leonard Cohen, plus boa.

Tom modelling stunning royal blue headwear.

Heidi being devoured by a carnivorous worm.

limell', Nick, and CZ. These hats all have darling mouse ears. All the rage for certain "Clubs" in 1957.

Jeanne, Stage Madame. "Fine – Don't Believe Me!"

Now we know whose fault it really was.

We'd love to hear your thoughts on this. Please join the conversation on our Facebook page. (https://www.facebook.com/m2mtucson/posts/831877573682447)

--------

Music Theory &

Exotic Scales: Part 3

In previous blogs in this series, we’ve described musical scales all based on western ideas of 12-tone chromatic scales (no micro-tones). Here I’ll fill out the exercise with more neat exotic stuff, and finish with Melodic Minor, which is very common in western music. Somehow, scales that are common in western music just aren't very interesting to M2M.

Double Harmonic Major (aka ''Arabic Scale''). Misirlou is perhaps the only tune known in the West that uses this scale (and even then only in the first part). It begins in E Double Harmonic Major, but changes to A harmonic minor.

C Double Harmonic Major: C, Db, E, F, G, Ab, B, (c)

Intervals (rel to Cmaj): 1, b2, 3, 4, 5, b6, 7, 8

Semi-tones: 1, 3, 1, 2, 1, 3, 1

(With TWO augmented 2nds, it feels like it has two root notes. Notice that the semi-tone sequence is palindromic.)

Wikipedia also says it was used, ”…in the “Bacchanale” from the opera Samson and Delilah by Saint-Saëns. Claude Debussy used the scale in "Soirée dans Grenade", "La Puerta del Vino", and "Sérénade interrompue" to evoke Spanish flamenco music or Moorish heritage. In popular music, Ritchie Blackmore of Deep Purple and Rainbow used the scale in pieces such as "Gates of Babylon" and "Stargazer". The Miles Davis jazz standard "Nardis" also makes use of the double harmonic."

Hungarian Minor (aka ''Gypsy Minor'' and ''Double Harmonic Minor''), is probably most important in Eastern European music.

Take the IVth mode of the Double Harmonic Major, that is, start on the F of the C double harmonic major scale:

F Hungarian Minor: F, G, Ab, B, c, db, e, (f)

Intervals (rel to F Maj): 1, 2, 3b, 4#, 5, 6b, 7, 8

Semi- tones: 2, 1, 3, 1, 1, 3, 1

(You could think of the key signature as Ab and Db, or G# and C#.)

Another example:

C Hungarian Minor C, D, Eb, F#, G, Ab, B, (c)

Intervals (rel to C Maj): 1, 2, 3b, 4#, 5, 6b, 7, 8

Semi- tones: 2, 1, 3, 1, 1, 3, 1

(You could think of the key signature as F#, Ab, and Eb.

Hungarian Minor Scale in C

Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 13 has runs in Hungarian Minor. That sharped (augmented) 4th interval is apparently very significant to Eastern European music. I think that a run with two semitones in a row should be easy to detect.

Hungarian Scale or Hungarian Gypsy can also refer to a scale of 2, 1, 3, 1, 1, 2, 2. Wikipedia says, "Other modern examples of these scales in use are Foreigner's "Blue Morning Blue Day" where both forms of the scale are used (the lowered 7th only occurring at the very end), and even more recently, Arctic Monkeys' "Brianstorm," where both forms of the scale are also being used, interchangeably."

Melodic Minor is a little more complicated than Harmonic Minor and might be a little happier sounding. It is rather European/Western. The melodic minor scale takes the major scale and flats the 3rd interval when ascending, and flats the 3rd, 6th, AND 7th when descending. This descent is the same as the natural minor scale.

Melodic Miner adjusting his condenser mic prior to blasting a seam.

the A melodic minor scale

The melodic minor scale in A looks like this:

Ascending: A, B, c, d, e, f#, g#, (a)

Interval (rel to A maj): 1, 2, b3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

Semi-tones: 2, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 1

(this is A major but with the 3rd flatted)

Descending: a, g, f, e, d, c, B, (A)

Interval (rel to A maj): 8, b7, b6, 5, 4, b3, 2, 1

Semi-tones: 2, 2, 1, 2, 2, 1, 2

(this is A natural minor in reverse )

Wikipedia cites Elton John's Sorry Seems To Be The Hardest Word as an example of the use of melodic minor. On Quora, Masaki Okamoto reminds us that certain lines in Greensleeves, Yesterday, Autumn Leaves, Lullaby of Birdland, The Shadow of Your Smile, I Just Called To Say I Love You, Nature Boy, When You Wish Upon a Star, and I Hear a Rhapsody use the melodic minor scale. I assume there are many more.

We'd love to hear your thoughts on this. Please join the conversation on our Facebook page.

(https://www.facebook.com/m2mtucson/posts/862704337266437)

--------

Cimbalom: History &

Repair, Part 1 of 4

This blog will give a little history of the cimbalom and document the steps I have taken to restore one example of the instrument to playability. It must be said up front that this one has had a hard life and cannot be viewed as a museum piece, but it is now stable, tunable, pretty, and sounds great. The dampers still need some adjustment, but all it needs is a player.

In April 2018, George Szigeti of New Mexico got in touch with The Folk Shop in Tucson, AZ saying he wanted to find a home for a cimbalom that had been in his family. He had been trying, unsuccessfully, to find someone who could fix it, and ended up calling The Folk Shop, and they called me. He did not want any money for it, just to get it repaired and back to being played - if possible. My personal problem is that nothing looks impossible, even when it should. For the purposes of this blog I’ll call it “mine,” but it is really being held in trust for someone who can play it.

According to George, this instrument belonged to one Danny Duna, who played it professionally, calling himself “The Last Gypsy in Bridgeport, Connecticut.” Danny gave it to George’s sister, who passed it to George’s father, who replaced the cracked wooden hitch-pin block where the wire strings dead-end. The instrument spent some time with the family in Maine, and later George’s father hauled it to St. Louis. Eventually, this block also failed. I have removed the old block and replaced it with one made of Baltic birch plywood, that will not crack. (Ha!) After a lot of cleaning, regluing, and some painting, it is ready.

So…. What IS a CIMBALOM? Imagine a hammered dulcimer on steroids. According to Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cimbalom

“The cimbalom is a type of chordophone composed of a large, trapezoidal box with metal strings stretched across its top. It is a musical instrument commonly found in the group of Central-Eastern European nations and cultures, namely contemporary Hungary, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Croatia, Romania, Moldova, Ukraine, Belarus and Poland. It is also popular in Greece and in gypsy (sic) music. The cimbalom is (typically) played by striking two beaters against the strings.” …” Moreover, the instrument name “cimbalom” also denotes earlier, smaller versions of the cimbalom, and folk cimbaloms, of different tone groupings, string arrangements, and box types.

In English, the cimbalom spelling is the most common, followed by the variants, derived from Austria-Hungary’s languages, cimbál, cymbalom, cymbalum, țambal, tsymbaly and tsimbl etc. Santur, Santouri, sandouri and a number of other non-Austro-Hungarian names are sometimes applied to this instrument in regions beyond Austria-Hungary which have their own names for related instruments of the struck zither or hammered dulcimer family.

According to ROMBASE, didactically edited information on Roma, http://rombase.uni-graz.at/cgi-bin/art.cgi?src=data/music/countries/hungary.en.xml, the connection with Roma music goes way back.

Though there were mentions made of Romani musicians in Hungary in 1489 and then in 1525, both in books of accounts of princes, the occupation did not become widespread among Roma before the latter half of the 18th century. Two famous musicians of the 18th century were Mihály Barna and Panna Cinka (?-1772). The four-member band of the latter consisted of two violins (lead: prím and kontra), a cimbalom and a double-bass. The composition of a typical "Gypsy band" including the former foursome and a clarinet later was patterned upon the serenade bands of Vienna.

Encyclopedia Britannica https://www.britannica.com/art/cimbalom says this:

“The modern cimbalom was invented in Budapest about 1870 by Jozsef Schunda. Some 20 years later it was proclaimed the national instrument of Hungary, and by 1897 courses in cimbalom instruction were offered at the Budapest Academy of Music. Franz Liszt introduced the cimbalom as an orchestral instrument in his Ungarischer Sturmmarsch (1876), and it was later used by Igor Stravinsky in Le Renard (1916) and Ragtime (1918) and by Zoltán Kodály in Háry János (1926).”

This modern cimbalom looks very much like “mine” (from https://ringve.no/en/cimbalom). This is the audience view - the player sits on the wide side and can reach a pedal that raises the damper bars that keep the strings from ringing for minutes. It has the mitered corners and slightly fluted legs (some models have rounded corners, blonde legs, and latches for a cover.) The Schunda company put its name in embossed letters on a plaque on the front of some. Here is a link to another photo: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cimbalom#/media/File:Cimbalom_(from_Emil_Richards_Collection).jpg

This photo is from Arnold Zwicky’s blog, https://arnoldzwicky.org/2015/12/09/piano-rag-music-ragtime/ showing one being played. The strings are struck with mallets the same way they are on the hammered dulcimer, although they are longer and the grip is different.

The cimbalom also has its western proponents.

http://soundproofedblog.blogspot.com/2014/06/cimbalom-nick-tolle.html. This is an interview with a U.S cimbalom player. Here is his web page: https://www.nicholastolle.com/. Richard Moore, of Canada is another western performer; here is his web page: http://www.cimbalom.ca/cimbalom_history.aspx. Matthey Colley, of Iowa, is also a proponent: http://www.studiozstpaul.com/blog/interview-with-matthew-coley-marimba-cimbalom.

How does it sound? There are many fantastic performances on YouTube. Some of these include the following: "Hungarian gypsy Street Musicians (Cimbalom) - Copenhagen, August 2014 (Part 1)" see also Parts 2 and 3 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N63gikqYyWI. They play "Fur Elise", "Caravan", and "Minor Swing" by Django Reinhardt. The instrument on this one looks just like "mine" with the surround removed. The dampers are the same and the wood in the frame is the same. The legs on “mine” are a little different. Note how the dampers are pumped.

"Nicoleta Tudorache & Vadar -Program de virtuozitate la tambal." https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DcCuwMYduEU&list=RD7CbTZB7Z4WA&index=25. Most of the performers are men, but women also play. A great performance of "Czardas" done blazingly fast!

In a different video, George, from Romania, in “Cimbalom street performance, Stockholm” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DJiIasbzKqI, George does "Love Story", "Fur Elise", and "Autumn Leaves". Fast! The surround is missing from his instrument, which is perhaps newer those in used by the “Hungarian gypsy street musicians” I mentioned above.

“Flight of the Bumblebee by Giani Lincan - cimbalom version”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_cXw8JRdui0&list=RD7CbTZB7Z4WA&index=18 Phenomenal.

“Game of Thrones Kaboom Cover” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q3PgF3AZKpo&list=RD7CbTZB7Z4WA&index=27. One Cimbalom for four hands.

Repair introduction:

The instrument has a trapezoidal “looks cover” that I call the “surround,” that has little function other than to provide handholds for transportation and setup. The legs have large wooden threads that go in wooden blocks screwed onto the base, so the legs can be removed for transportation, as can the damper-pedal support. George had removed all this stuff so he and his wife could load it into their car and so he and I could get into our car (with the help of some nice passers-by who thought this was fascinating). We met in Lordsburg, NM for the transfer on a very hot, very dry day. I took it all home, wrestled it into my shop and started to fix it up.

The main problem. This is the end of the hitch-pin block that George’s father installed.

It was an expertly fitted piece of poplar, but the grain of the piece had an unfortunate orientation. When a green log is dried, it tends to split radially from the bark toward to tree’s center, exactly the way this board did. There are five big carriage bolts pulling the left side down, and all those strings are pulling up and to the right in the middle, via the hitch pins visible here. The string force is partly resisted by the block at the right edge of the photo. I thought about cleaning up the crack and dowelling the two halves back together, but figured a) the block was badly splintered so the joint might not be strong enough, and b) only the upper surface shows, so c) why not use a big block of plywood and stain the top surface?

Next time I will show the fitting of the new hitch-pin block.

More detail of the failed hitch-pin block. It sits on a pine wedge and has 124 heavy pins (hitch-pins) driven into the top to hold the strings. The red circles are felt washers that hide the crushed wood where the pins are pulled by the string force. At the bottom is the base, consisting of about 2 inches of pine plus about 1 inch of hardwood (perhaps live oak?) The bolt shown is used to hold and adjust one end of one of the damper bars.

George kindly included some new and used mallets, instruction books in Hungarian, spare music wire, and some spare parts. The subsequent installments of this blog will illustrate the steps that were necessary to get it playing again.

If anyone out there has any information about Danny Duna or his performances, please share them with us at M2Mtucson@gmail.com. If we can use it, we’ll send you a copy of our CD.

We'd love to hear your thoughts on this. Please join the conversation on our Facebook page.

(https://www.facebook.com/m2mtucson/posts/1435230973347101)

--------

Cimbalom: History &

Repair, Part 2 of 4

In the first installment, I outlined what a cimbalom is and how this one came to be in my hands. Here, I’ll show how it all came apart for repair. Everything needs to be quite strong because the force of all those strings (124 of them) is on the order of 1.2 ton.

Here is the main problem (repeated from the first blog installment): this angled block of wood, called the hitch-pin block had completely failed and needed replacement.

Here is the main problem (repeated from the first blog installment): this angled block of wood, called the hitch-pin block had completely failed and needed replacement.

The hitch-pin block sits on a pine wedge and has 124 heavy pins (hitch-pins) driven into the top to hold the strings. At the bottom is the base, consisting of about 2 inches of pine plus about 1 inch of hardwood (perhaps live oak?)

This is the tuning pin block at the side opposite from the hitch-pin block. It looks like elm to me. Here, the strings have been coiled out of the way, rather than removed from the pins. Notice the washer and carriage bolt. There are five of them holding the block to the base.

Before the strings were coiled, I photographed everything so I could replace the bridges. The cracks in the soundboard are obvious and were caused by shrinkage. The wooden mushrooms are the bridge supports. Think hammered dulcimer.

The top and bottom edges of the soundboard (painted black) are held by battens and screws. I suspected, from the many screw holes, that the soundboard had been replaced. This suspicion was confirmed when I examined the soundboard braces. The flathead screws under the battens are the reason the soundboard cracked – there was no allowance for expansion/contraction with humidity changes in the soundboard and it had nowhere to go. I have put the batten screws back loosely, with large holes in the soundboard, and have left the flathead screws out.

Coiling the strings above the tuning pins. Other than the confusion and labeling mess dealing with 125 strings, there was the problem of possibly breaking the ends (“beckets”) off the strings, so I chose to leave them attached to the tuning pins. Some of the other soundboard cracks are visible.

All strings coiled and out of the way. Hitch-pin block removed.

The hitch-pins did not come out easily. This is part of why the block cracked; the pins had been hammered into small holes and the wedging added to the stress on the block. All the pins had to have rust, pry-bar scars, and mushrooming removed before they could be reinstalled in the new hitch-pin block. Power de-scaling with Scotch-Brite™ did the trick.

The insides, with the soundboard off and the hitch-pin block removed. At each end is an aluminum “shoe” that distributes the string forces from the tuning pin and hitch-pin blocks onto the two 1” diameter solid steel support posts. From the lengths and diameters of the strings I calculated that they had tensions between 7 and 15Kgm each, and there are 124 of them. At an average of 10Kgm, that would total 1240Kgm or 2730lb or 1.2 tons of force between the two blocks. No wonder they used all that steel!

In the previous photo, the 19 soundposts are visible. Originally, the instrument had 19 round soundposts about 5/8” in diameter. The impression of one is visible just above the newer, rectangular soundpost labeled “15” at the bottom. Also visible are the two notes from previous repairers and the original label (white.) After the soundboard and the braces were repaired, the soundposts were removed and adjusted to the proper lengths, then reglued. Some, particularly those at the tuning pin end, had to be repositioned to sit correctly below the crossings of the braces.

Original label. Someone tried to scrape it off, and I have no idea why there are knife cuts around and through it. The “New York City” might indicate that it was imported by a branch of the Schunda company, but I am just guessing. The date might be 1929. Black Tuesday was October 29, 1929, after which importing such a luxury item would have been unlikely, but on September 10th, people were still optimistic. It might also be 1919. V.J. Schunda died in 1923, so 1929 is less likely. We might never know.

Repairer’s note from 1979

Repairer’s note from 1962.

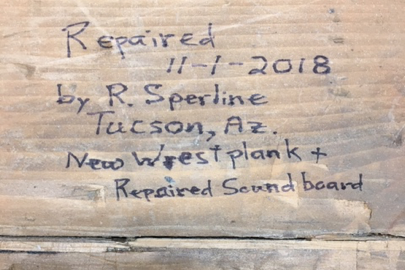

Repairer’s note from 2018. In this photo, I mistakenly called the hitch-pin block a “wrestplank”

In the next blog installment, I will show reconstruction of the soundboard.

We'd love to hear your thoughts on this. Please join the conversation on our Facebook page.

(https://www.facebook.com/m2mtucson/posts/1441002012769997)

--------

Cimbalom: History &

Repair, Part 3 of 4

In this installment, I’ll show reconstruction of the cimbalom’s soundboard. All those strings under all that tension creates a LOT of downforce on the soundboard and soundposts. The soundboard is spruce, about 5/16” thick. The braces are some very dense blonde hardwood that smells fruity when scraped, so, given where it originated, is likely apricot.

Underside of soundboard with hardwood braces, when the instrument was opened.

Detail of underside of soundboard showing at least two types of failed glue that had to be removed before the soundboard could be fixed. Notice the crushed spots at the brace crossings where the soundposts were too long. I also made my own set of pencil marks, trying to stay organized.

From the shadows and knife marks, we see further evidence that this is not the original set of braces for this soundboard. In addition, judging from the positions of the replacement soundposts, I don’t think these are the original braces for this instrument. I call this “forensic luthierie.”

The braces didn’t fit very well, so the adhesive made little pedestals. This particular stuff was beige. An earlier adhesive appeared to be hide glue, which is amber colored and gets brittle when old. The hide glue appears as amber puddles toward the left side. (Rant follows: “glue” properly refers only to that made from animal tissue. All others are “adhesives” or “cement.”)

Cleaning and reassembling the soundboard. Notice the several sets of holes at the edge. I had to make a few more, and fill some, to get it right.

Gluing up the soundboard with a combination of guitar clamps and bar clamps. The outside surface had to be kept level and flush while the edges were pressed tightly together, so everything was positioned with the aid of a solid-core door and lots of non-stick plastic.

Soundboard reglued, braces cleaned and reglued. I filled the wounds in the front with black filler, sanded a lot, then painted it satin black. Now that we see how the braces are arranged, they cannot be glued to the soundboard along their entire lengths, or the soundboard will just split again with the first dry weather. I glued the vertical stays to the soundboard only at the centers, and glued the horizontals only to the verticals where they crossed. This allows the soundboard to expand and contract in the crossgrain direction and slide over the braces except in the middle. At the ends, the loose screws allow the soundboard to move more or less freely.

Drilling the new laminated hitch-pin block for the 124 pins. The holes are angled so the string loops stay against the wood when tightened. The block is several layers of Baltic birch plywood laminated with epoxy.

Fitting the new hitch-pin block. A tapered wedge gets inserted at the upper end to facilitate the fitting. The block must simultaneously press on the upper and lower wooden supports and the aluminum shoes that carry the force to the steel poles. One aluminum shoe has been attached to the block with screws.

Trimming the fitted hitch-pin block by hand because it was too long to fit in the bandsaw. With the ryoba nokogiri I can do this type of cut such that it needs neither planning nor sanding after sawing. I’ve used this one saw since 1980 and it has never needed sharpening.

Trimmed, stained, and installed. Note the wedge at the left end. There is still some masking tape and paper from spray painting some areas silver that will be visible at the ends of the soundboard.

We'd love to hear your thoughts on this. Please join the conversation on our Facebook page.

(https://www.facebook.com/m2mtucson/posts/1446703862199812)

--------

Cimbalom: History &

Repair, Part 4 of 4

This is the final installment of the story of bringing one cimbalom back to life. It was starting to look promising, as the strings went back on, but, of course, another problem appeared just as everything was brought up to tension — the base was cracked on one side. I’m better with tiny tools than with steel, but I’m dangerous with a calculator, so I could figure out just how must steel would fix it.

Starting to put the strings back on. The silver circles are a washer and the head of one of five 5/16” carriage bolts that hold the block to the base. The tuning pin end is similar. Notice the mushroom-shaped bridge risers with brass saddles on top, and the small brass nuts sitting on the hitch-pin block. Some of these nuts were missing, so I soldered some from brass rod and strip. Whoever made up the highest strings twisted the loops the wrong way — the ends face left, whereas on all the other strings they face right. It doesn’t matter to the strength, just to some of us nit-pickers.

Nearly all strung up. There are still a few strings missing. George gave me a kit that included used and new mallets, stray parts, some tools, and supplies of a few gauges of piano wire. I am using the piano wire to create new plain strings and to splice the broken ends of several of the wound strings. One reason there were so many broken strings was that the tuning wrench (aka “tuning hammer”) he had was for larger tuning pins, so it slid down too far on the pins and hit the strings right where they were bent to fit into the tuning pins (the “becket”.) This contact wore them thinner right where they have the most stress. My father had given me a tuning hammer that fits better, so the larger one is going into a drawer.

Restrung and tuned (there are still a couple of bass strings unrepaired.) This is the tuning-pin end.

After it was up to tension, I noticed this crack at the right treble (audience) edge. The 1” thick hardwood brace under the 2” thick pine base (three layers thick) is cracked through, and the bottom pine layer is cracked. The location is where a big woodscrew goes diagonally up into the surround from a pocket cut in the hardwood brace. Notice how the entire base is bent under the tuning pin block. The yellow wood between the base/brace and the dark base for attachment of a leg was previously added to make up for the fact that the surround seems too tall for this instrument’s core. One possibility is that the surround has been replaced. A second possibility, suggested by the assortment of screw holes in the base at the corners, is that the leg-base blocks have been replaced and were mis-located. A third possibility is that Danny Duna had long shins. What did Sherlock Holmes say?

Detail of the crack in the base at the right treble end.

Similar crack and bending of the base at the left end of the treble edge. The gap between the base and the hitch-pin block (extreme lower right of photo) was alleviated by tightening the carriage bolts.

Detail of crack in the base brace at the left treble edge. Ugly, no?

The solution for the cracks in the base at the treble edge; channel out a slot for insertion of a thick-walled 1”x1” steel tube, to be attached by the end two carriage bolts. Here’s only one of the two bolts that have been exposed. Using on-line information and standard engineering equations involving moments of inertia, moduli of elasticity, and deflection, I calculated that this tube would deflect ¼” at its center with 586 lb. of force. Because most of the bending occurs in the last ¼ of its length there should be very little flexure where the cracks are. (Applying the force at the ¼ point rather than at the ½ point gives 8 times the stiffness!) Notice the two pockets cut in the brace at the top edge some time in the past – those pockets were where the cracks appeared. At the lower middle are the two levers that translate downward motion of the damper pedal into upward motion on two rods that lift the damper bars.

Detail of the slot/pocket for the 1” steel tube reinforcement. I used an oscillating saw to make the blind cuts and a chisel to do the final adjustments. Trimming the steel tube to length by hand with a hacksaw required more labor than all the rest of this operation. 🤯

Detail of how the surround was attached to the base. At six places, a plywood shim was glued to a hardwood block, the shim slid between the surround and the base, and the block screwed to both the surround and the base. The shims filled the big gaps between the surround and the base, where a few screws had been holding things together with a lot of wishful thinking. Each leg is matched with a numbered socket, because they have four unique lengths and angles. (There have been several such numbering schemes written on the legs over the years, only one of which now works.)

Detail of one of the two old pockets where the cracks were, showing the steel tube brace in place. The thin plywood shim and hardwood block form a hook that solidifies the structure when the instrument is picked up by the surround. (I’m trying to make it easier on the roadies - this instrument is a beast and hard to hold.)

Detail of left side damper bar. The felt pads touch the vibrating lengths of the strings most of the time to keep them from ringing incessantly. The bars are notched to jump over the tail ends of strings. At the right of the picture, the bar is notched to account for the courses being at different heights.

The dampers (one on each side) are raised by pressing the single damper pedal, allowing the strings to ring. The action is similar to that of the right-hand pedal on a piano. To move the instrument, the pedal is unhooked and unbolted from the bottom of the case, then the legs are unscrewed from their sockets. Two roadies then boost the entire 185 lb. (est.) into the conveyance of your choice. Tell them not to forget the pedal or the legs. You should take care of the mallets and the tuning hammer.

Et voilà!

Tuned, surrounded, reinforced with steel, and standing on its own legs in my living room. Last spring, when it all came together, all I would say with confidence was “At least it is pretty.” Now, after a year, it is still basically in tune and not cracking, so I’m declaring it well and truly fixed. Someone, someday, should build it a cover.

R. Sperline

Tucson, Arizona

We'd love to hear your thoughts on this. Please join the conversation on our Facebook page.

(https://www.facebook.com/m2mtucson/posts/1452671138269751)